From China's Xinhua News:

This kind of news isn't surprising. I hear all the time from young people in Xi'an about graduates from last year's university class who still can't find work. There are about to be several more million fresh graduates entering the job market in a few weeks also looking for jobs. Times are looking bleak for educated Chinese young people trying to find work doing what they studied at university.

Image from Ernop's Flickr page

BEIJING, May 31 (Xinhua) -- China expects fewer students to participate in the upcoming three-day annual college entrance exam this year, according to Sunday version of China Daily.

The college entrance exam has been seen as the make-or-break benchmark for millions of Chinese young people since 1977.

Minister of Education Zhou Ji had predicted that the overall number of applicants would exceed 10 million -- last year's total was 10.5 million -- but figures from local governments suggest the number of students taking part may be far fewer, the newspaper said.

In Shangdong, a provincial economic powerhouse, education officials said they received 100,000 fewer applicants this year than they did in 2008 -- a drop of more than 10 percent.

...

"Since the financial crisis last year, the grim employment situation has broken the 'employment myth' for those with a college degree. Some students changed their minds about getting a good job through higher education. They simply quit (from taking the exam)," an anonymous recruitment officer with the Beijing Institute of Technology was quoted as saying.

Read the Entire Article

This phenomenon of people questioning the value of high-level education is not limited to China. America is currently undergoing a similar debate.

An article from last week's New York Times' Magazine - "The Case for Working With Your Hands" - does a great job talking about the more academic life young Americans have been molded for and the more labor intensive jobs that they are told to avoid.

Here's the beginning of the article:

The television show “Deadliest Catch” depicts commercial crab fishermen in the Bering Sea. Another,“Dirty Jobs,” shows all kinds of grueling work; one episode featured a guy who inseminates turkeys for a living. The weird fascination of these shows must lie partly in the fact that such confrontations with material reality have become exotically unfamiliar. Many of us do work that feels more surreal than real. Working in an office, you often find it difficult to see any tangible result from your efforts. What exactly have you accomplished at the end of any given day? Where the chain of cause and effect is opaque and responsibility diffuse, the experience of individual agency can be elusive. “Dilbert,” “The Office” and similar portrayals of cubicle life attest to the dark absurdism with which many Americans have come to view their white-collar jobs.This article's author, Matthew B. Crawford, makes some really keen observations and criticisms of the life Americans, and more and more Chinese, idealize as "getting ahead."

Is there a more “real” alternative (short of inseminating turkeys)?

High-school shop-class programs were widely dismantled in the 1990s as educators prepared students to become “knowledge workers.” The imperative of the last 20 years to round up every warm body and send it to college, then to the cubicle, was tied to a vision of the future in which we somehow take leave of material reality and glide about in a pure information economy. This has not come to pass. To begin with, such work often feels more enervating than gliding. More fundamentally, now as ever, somebody has to actually do things: fix our cars, unclog our toilets, build our houses.

When we praise people who do work that is straightforwardly useful, the praise often betrays an assumption that they had no other options. We idealize them as the salt of the earth and emphasize the sacrifice for others their work may entail. Such sacrifice does indeed occur — the hazards faced by a lineman restoring power during a storm come to mind. But what if such work answers as well to a basic human need of the one who does it? I take this to be the suggestion of Marge Piercy’s poem “To Be of Use,” which concludes with the lines “the pitcher longs for water to carry/and a person for work that is real.” Beneath our gratitude for the lineman may rest envy.

This seems to be a moment when the useful arts have an especially compelling economic rationale. A car mechanics' trade association reports that repair shops have seen their business jump significantly in the current recession: people aren't buying new cars; they are fixing the ones they have. The current downturn is likely to pass eventually. But there are also systemic changes in the economy, arising from information technology, that have the surprising effect of making the manual trades — plumbing, electrical work, car repair — more attractive as careers. The Princeton economist Alan Blinder argues that the crucial distinction in the emerging labor market is not between those with more or less education, but between those whose services can be delivered over a wire and those who must do their work in person or on site. The latter will find their livelihoods more secure against outsourcing to distant countries. As Blinder puts it, “You can’t hammer a nail over the Internet.” Nor can the Indians fix your car. Because they are in India.

If the goal is to earn a living, then, maybe it isn’t really true that 18-year-olds need to be imparted with a sense of panic about getting into college (though they certainly need to learn). Some people are hustled off to college, then to the cubicle, against their own inclinations and natural bents, when they would rather be learning to build things or fix things. One shop teacher suggested to me that “in schools, we create artificial learning environments for our children that they know to be contrived and undeserving of their full attention and engagement. Without the opportunity to learn through the hands, the world remains abstract and distant, and the passions for learning will not be engaged.”

A gifted young person who chooses to become a mechanic rather than to accumulate academic credentials is viewed as eccentric, if not self-destructive. There is a pervasive anxiety among parents that there is only one track to success for their children. It runs through a series of gates controlled by prestigious institutions. Further, there is wide use of drugs to medicate boys, especially, against their natural tendency toward action, the better to “keep things on track.” I taught briefly in a public high school and would have loved to have set up a Ritalin fogger in my classroom. It is a rare person, male or female, who is naturally inclined to sit still for 17 years in school, and then indefinitely at work.

Read On

In the not too distant past, I meditated (or was it ranted) about the idea of "getting ahead" in contemporary society. I came to the conclusion that the dreams and idealizations that I'd been fed from the time I was a child may have been the product of a society that had lost complete touch with reality. Based on the state of the the US' economic system and the state of its people, I feel justified in questioning how involved I want to get with "The American Dream": a house with a white picket fence and a mortgage, 3.18 children, etc.

I did participate in America's university system. I even got a worthless degree: a bachelor's degree in philosophy. I have student loans still to pay off.

I don't regret my decision to pursue a higher education. In getting a degree that fostered independent thought and developed my mind, I feel as though the education I received was invaluable. My degree isn't going to knock down to many doors in future job applications, but it was a very beneficial thing for my life.

At this point in time though - the summer of 2009 - I completely understand a young adult at the crossroads of life deciding against spending four years of his or her life in a college or university that wants to prepare him or her for a life of sitting in a cubicle.

As the NY Times article posits, skipping a traditional four year university doesn't mean one has to stop learning. I'm very much in support of learning a trade or specialized skills if one chooses against the more cubicle-based path. I'm definitely not against education and learning.

I do feel that the current status of the world and its economic systems calls for young people to reassess the assumptions about where they will fit in the world economy in the years to come though.

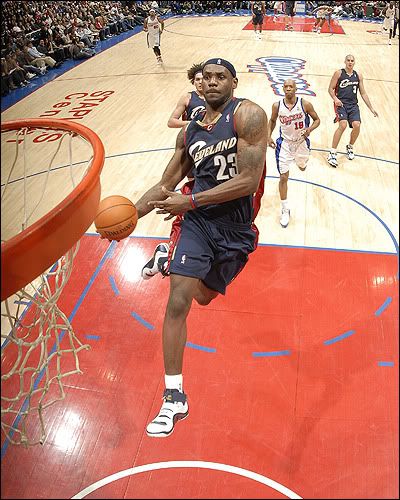

According to multiple sources within the Cavs, franchise majority owner Dan Gilbert has a tentative agreement in place to allow a group of Chinese investors to purchase a significant stake in the Cavaliers Operating Company, the entity that owns the Cavs and operates Quicken Loans Arena. The group is led by JianHua (Kenny) Huang, a Chinese businessman who has become successful by linking American and Chinese companies.

According to multiple sources within the Cavs, franchise majority owner Dan Gilbert has a tentative agreement in place to allow a group of Chinese investors to purchase a significant stake in the Cavaliers Operating Company, the entity that owns the Cavs and operates Quicken Loans Arena. The group is led by JianHua (Kenny) Huang, a Chinese businessman who has become successful by linking American and Chinese companies.  "This has recently happened again. As has been done previously, we're in the process of reviewing the possibility presented to us. Beyond that, we do not feel it would be appropriate to give further comment at this time."

"This has recently happened again. As has been done previously, we're in the process of reviewing the possibility presented to us. Beyond that, we do not feel it would be appropriate to give further comment at this time."